Learning Theory: Cognitivism

Exploration of cognitivism, which includes theories from Piaget, Vygotsky, Bruner, and Bandura. Cognitive Load Theory is also reviewed and applied to instructional design.

Overview of Cognitivism

Cognitivism emerged as a response to the limitations of behaviorism, shifting the focus from observable behavior to the internal mental processes involved in learning. Rather than viewing learners as passive responders to external stimuli, cognitivist theory sees them as active processors of information: Organising, storing, and retrieving knowledge based on what they already know.

Several foundational thinkers contributed to this shift:

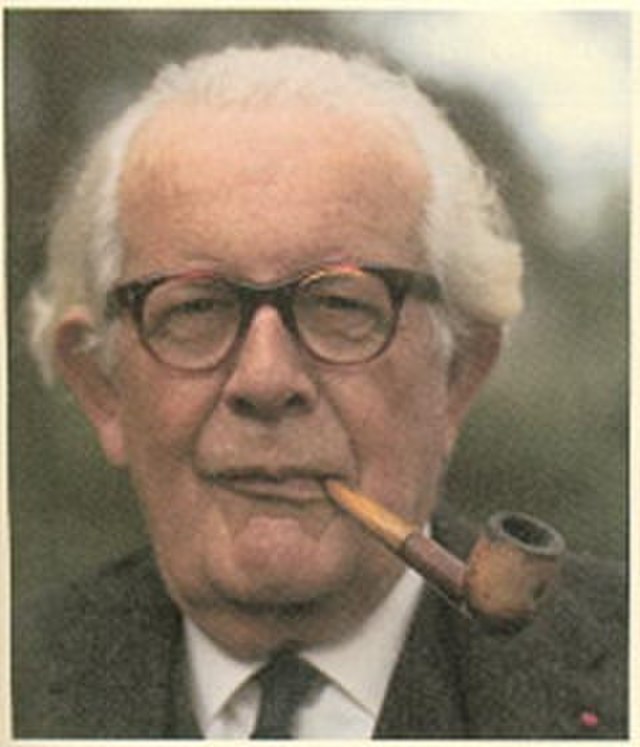

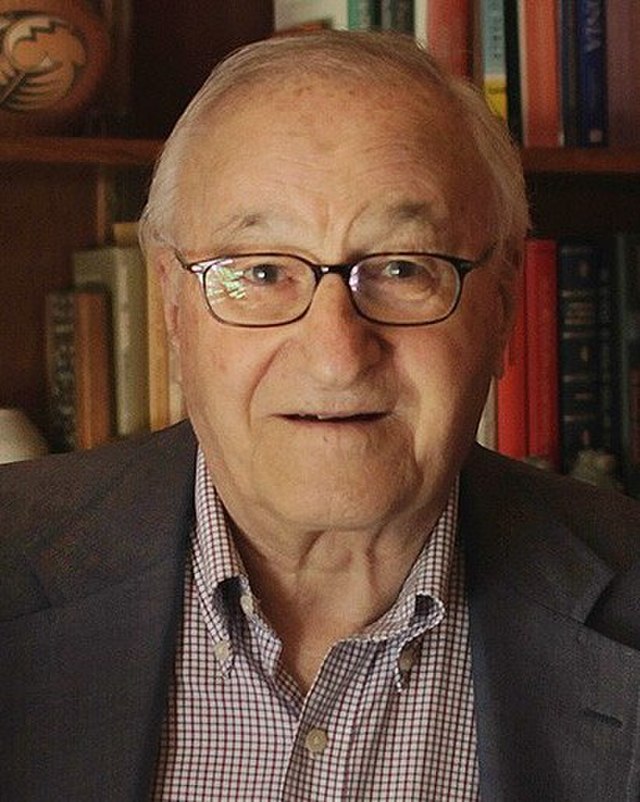

- Jean Piaget (1936)

Introduced the theory of cognitive development. Focused on how learners build mental models through stages of cognitive development. His work highlighted the importance of developmental readiness and how knowledge is constructed through interaction with the environment. - Lev Vygotsky (1978)

Introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), emphasizing the role of social interaction and guided learning (scaffolding) in advancing cognitive growth beyond what learners can do alone. - Jerome Bruner (1960)

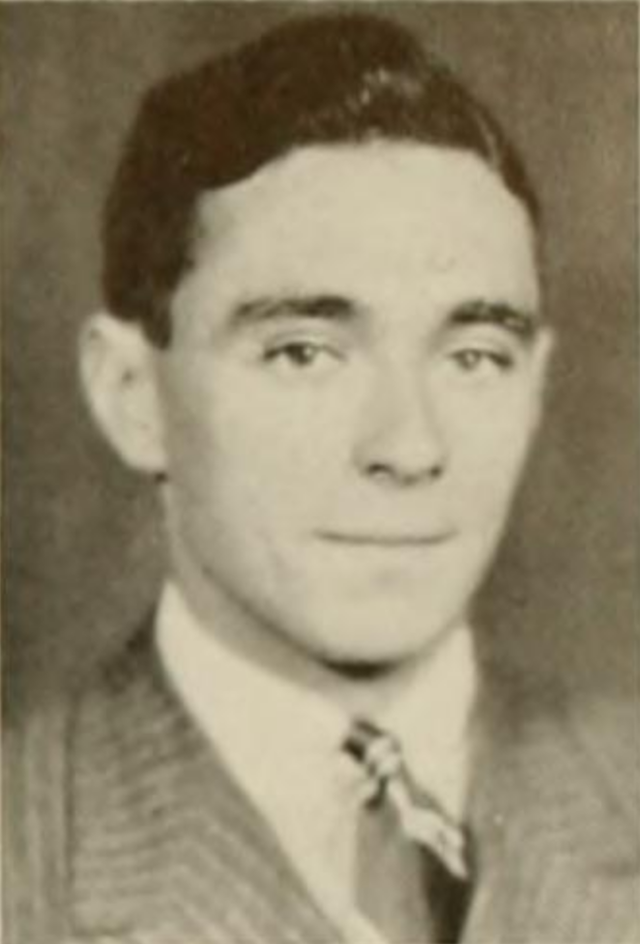

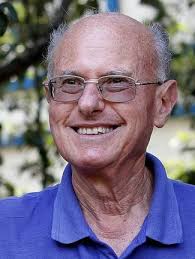

Advocated for discovery learning and argued that learners understand new ideas best when those ideas are built on what they already know. He introduced the idea of spiral curriculum, where complex ideas are revisited over time at increasing levels of difficulty. - Albert Bandura (1977)

Added the concept of social learning. The idea that people learn by observing others, not just through direct experience. His theory bridged behaviorism and cognitivism by recognising the role of modeling and internal processes in learning.

Another key development in the cognitivist framework is Cognitive Load Theory, introduced by John Sweller (1988). It focuses on how instructional design can either support or hinder working memory. The theory divides cognitive load into three types: intrinsic (inherent to the material), extraneous (caused by poor design), and germane (supportive of learning). Managing these types of load is essential for effective instruction.

"Cognitivism shifted the focus from what learners do to how they think, reminding us that memory, mental effort, and prior knowledge are just as critical as content when designing instruction"

Connections to teaching and learning

Cognitivism has had a major influence on how we design instruction, especially when the goal is understanding, not just performance. Where behaviorism focuses on reinforcement, cognitivism focuses on how learners take in, store, and organise information.

Each major theory introduced in this framework brings something specific to how we design and support learning:

- Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget proposed that learners construct knowledge through interaction with their environment and progress through developmental stages. This theory reminds us to align content with cognitive readiness, for example, avoiding abstract reasoning tasks with learners still in the concrete operational stage. In design terms, this means adjusting complexity, using concrete examples first, and scaffolding tasks based on the learner's stage of understanding. - Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory (Zone of Proximal Development)

Vygotsky emphasized that learning is social and happens most effectively just beyond the learner's current ability, within their Zone of Proximal Development. The key design takeaway is scaffolding, providing support such as prompts, guided examples, and step-by-step practice until the learner can perform independently. This is often seen in eLearning through tooltips, walkthroughs, or graduated task complexity. - Bruner's Discovery Learning and Spiral Curriculum

Bruner believed that learning is most effective when learners actively construct meaning and revisit concepts over time. His spiral curriculum approach encourages designers to sequence content so that learners return to key concepts with increasing complexity. It also supports strategies like activating prior knowledge and building instruction around real-world exploration, especially in self-paced or adaptive learning modules. - Bandura's Social Learning Theory

Bandura's theory shows that people learn by observing others, not just through direct experience. In instructional design, this justifies the use of video demonstrations, modeled behaviors, and scenario-based examples, especially in soft skills, customer service, or leadership training. Learners watch, interpret, and imitate what they see, even in digital environments. - Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory

Sweller argued that working memory has limits, and instructional design should manage how much information a learner processes at once. His theory divides cognitive load into intrinsic (complexity of the content), extraneous(design-related distractions), and germane (effort to build mental schemas). To manage this, we apply techniques like chunking, eliminating unnecessary content, using clear visuals, and providing worked examples before learners attempt complex tasks on their own.

"From developmental stages to memory limits, cognitivism gave us the tools to design learning that works with the mind, not against it. It's the reason we scaffold, sequence, and structure content the way we do"

Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget introduced the idea that children move through specific stages of cognitive growth. His work emphasized how learners actively construct knowledge and process experiences based on their developmental stage. This theory laid the foundation for instructional methods that align content with learner readiness.

The Process of Education

Bruner promoted discovery learning and the spiral curriculum, arguing that students learn best when they actively build on what they already know. His work emphasized the importance of structure, sequencing, and revisiting concepts to deepen understanding.

Social Learning Theory

Bandura expanded the cognitivist perspective by highlighting the role of observation and imitation. He showed that people can learn new behaviors by watching others, without direct experience, introducing modeling as an essential instructional strategy.

Cognitive Load Theory

Sweller introduced the concept that working memory is limited, and instructional design should minimise unnecessary mental effort. His theory separates intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load, forming the basis for how we structure content to avoid overload and improve retention.

Implications of Cognitivism for Instructional (Learning) Design

Cognitivism has shaped a big part of how I approach course structure, sequencing, and learner support. It reminds me that learning isn't just about showing the right behavior; it's about what's happening inside the learner's mind. That means our job isn't just to deliver content; it's to design in a way that supports how people take in, organize, and retain information.

I often use cognitivist principles when the goal is understanding or problem-solving; not just recall or task execution. For example, I'll intentionally sequence content from simple to complex, and I'll use advance organizers, concept maps, or pre-assessments to activate prior knowledge before new content is introduced. These aren't just nice add-ons; they're critical when designing for meaningful learning.

Cognitive load is another area where theory meets reality. If I see a slide packed with text or a module full of disconnected concepts, I know learners are going to check out. That's where Cognitive Load Theory comes in. I'll break down material into smaller pieces (chunks), reduce visual noise, and provide worked examples before asking for performance. These design decisions are directly tied to how memory works.

Cognitivism also changed how I think about feedback. It's not just about right or wrong; it's about helping the learner understand why. That might mean including a short explanation after a quiz response or offering a visual to clarify a misunderstanding.

Ultimately, cognitivism pushes me to design for thinking, not just doing. It shows up in how I scaffold content, structure interactions, and guide learners toward insight; not just completion. It's a mindset that supports deeper learning, especially when we want to go beyond surface-level performance.

Strengths and Limitations of Cognitivism

Corporate Training

In corporate training, cognitivism offers some real advantages,especially when the goal is comprehension, structured problem-solving, or transferring knowledge to new situations. It helps me design learning that isn't just task-focused, but built to support actual understanding.

Strengths

One of its biggest strengths is in helping employees make sense of complex systems or processes. When you're onboarding someone into a new role, teaching a product line, or rolling out a new tool, it's not just about getting them to follow steps; it's about helping them understand how things work and why. Cognitivist strategies like scaffolding, worked examples, and chunking are essential here. They reduce overload and build confidence as learners move from surface understanding to actual fluency.

Another strength is that it supports transfer of learning. If employees understand the underlying logic behind a workflow or a customer policy, they're better equipped to apply it in different scenarios. That's something behaviorism can't easily handle, and where cognitivism adds real value.

Limitations

But there are limitations. First, time and context matter. Many corporate environments want quick wins, short modules, measurable outcomes, and repeatable behaviors. In those cases, there's not always room for deep exploration or reflective learning. Cognitivist approaches can feel too slow or abstract if not handled carefully.

Second, it assumes learners are ready to engage mentally with content. But that's not always the case, especially in high-pressure or low-motivation settings. If the learner doesn't have the background knowledge or mental space to focus, even well-designed cognitive supports can fall flat.

And finally, it's easy to overdo it. If we throw too much structure, too many visuals, or too many strategies into one lesson, we end up doing the opposite of what the theory intends. We overload the learner. That's where Cognitive Load Theory helps keep things grounded: simplify the experience, don't just layer it.

"Cognitivism helps design smarter, more intentional training, but it has to be balanced. Even the best structured content won't land if the learner is just trying to get to the end and move on”

© Images from Wikimedia Commons in the public domain.